Lessons for the Long Term

Investigation into the Ministry of Long-Term Care’s oversight of long-term care homes through inspection and enforcement during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table of contents

Show

Hide

Lessons for the Long Term

Investigation into the Ministry of Long-Term Care’s oversight of long-term care homes through inspection and enforcement during the COVID-19 pandemic

Paul Dubé

Ombudsman of Ontario

September 2023

Office of the Ombudsman of Ontario

We are

An independent office of the Legislature that resolves and investigates public complaints about services provided by Ontario public sector bodies. These include provincial government ministries, agencies, boards, commissions, corporations and tribunals, as well as municipalities,

universities, school boards, child protection services and French language services.

Land acknowledgement and commitment to reconciliation

The Ontario Ombudsman’s work takes place on traditional Indigenous territories across the province we now call Ontario, and we are thankful to be able to work and live on this land. We would like to acknowledge that Toronto, where the Office of the Ontario Ombudsman is located, is the traditional territory of many nations, including the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee, and the Wendat peoples, and is now home to many First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples.

We believe it is important to offer a land acknowledgement as a way to recognize, respect and honour this territory, the treaties, the original occupants, their ancestors, and the historic connection they still have with this territory.

As part of our commitment to reconciliation, we are providing educational opportunities to help our staff learn more about our shared history and the harms that have been inflicted on Indigenous peoples. We are working to establish mutually respectful relationships with Indigenous people across the province and will continue to incorporate recommendations from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission into our work. We are grateful for the opportunity to work across Turtle Island.

Contributors

Director, Special Ombudsman Response Team

- Domonie Pierre

Lead Investigators

- Rosie Dear

- Chris McCague

Investigators

- Emily Ashizawa

- Armita Bahador

- Richard Francis

- Alex Giletski

- Yvonne Heggie

- Carmen Kallideen

- John O’Leary

- Karyna Pavlenko

- Dahlia Phillips

Early Resolution Officers

- Angela Alibertis

- Olivia Hannigan

- Claudia Rios

- Kirsten Temporale

Senior Counsel

- Robin Bates

General Counsel

- Laura Pettigrew

Press Conference

Executive Summary

1 Few lives have remained untouched by the COVID-19 pandemic. When this novel coronavirus emerged as a global pandemic in March 2020, many naively thought that it would take a few weeks to “flatten the curve” and then life would continue as normal. However, that initial optimism soon faded as new COVID-19 variants arose and wave after wave swept through the province. Up to May 5, 2023, when the World Health Organization declared an end to the global emergency status for COVID-19, the virus had claimed the lives of more than 15,000 Ontarians.

2 While each loss of life is a tragedy, certain high-risk and vulnerable populations were disproportionately impacted by the virus, including those working and living in Ontario’s long-term care homes. Between the start of the pandemic and April 2022, 4,335 long-term care residents and 13 staff members died from COVID-19, and more than 41,000 were infected.[1] The first wave took a particularly heavy toll at a time when little was known about the disease, or how to best contain or treat it. Close to 2,000 COVID-related deaths in the long-term care sector occurred during the first wave of the pandemic, from January 15, 2020 until August 2, 2020.

3 This report stems from the devastating “first wave” of the COVID-19 pandemic. It was a time when the world was still coming to terms with the rapidly spreading virus – and before Ontario’s response to the crisis was subjected to a series of reviews and recommendations for improvement. Since then, many significant changes have been made to shore up the province’s capacity to weather a similar emergency in future – but much more needs to be done to address the serious lapses in oversight I have detailed in this report. My investigation and recommendations have focused on evidence not revealed in other reviews, and the remedial action necessary to ensure Ontario is better prepared and its residents better protected when future crises arise.

4 Ontario has more than 600 long-term care homes, collectively comprising nearly 80,000 resident beds. Long-term care homes provide access to 24-hour nursing and personal care in a home-like environment. These services are crucial to maintaining the health and dignity of residents, the vast majority of whom need extensive help with daily activities such as getting out of bed, eating or toileting, and experience some form of cognitive impairment or neurological disease. Long-term care homes are overseen by the Ministry of Long-Term Care, which is responsible for licensing the homes, receiving complaints, conducting compliance inspections, and taking enforcement action if a home is not complying with legal requirements. In addition to the Ministry of Long-Term Care, other organizations oversee long-term care homes, including the Ministry of Health, local public health units, and Ontario’s Patient Ombudsman.

5 As the first wave of the pandemic unfolded, and COVID-related deaths surged in the sector, my Office was inundated with 269 complaints and inquiries. In an exceptional move, Canadian Armed Forces personnel were deployed to assist several Ontario long-term care homes that were experiencing crisis. In May 2020, it was reported that Armed Forces personnel had witnessed shocking living conditions in these homes.

6 Given the grave situation evident in the long-term care sector, on June 1, 2020, I initiated an investigation on my own motion into the Ministries of Health and Long-Term Care’s oversight of the sector during the pandemic. At the time, I announced that my investigation would focus on how the two ministries ensured the safety of long-term care residents and staff. Although my Office has broad investigative authority over ministries and the Patient Ombudsman, my authority does not extend to individual long-term care homes, their staff, or public health units.

7 As the pandemic continued to rage through the province, other bodies, including the Long-Term Care COVID‑19 Commission and the Auditor General, undertook their own comprehensive investigations and reviews. After considering the areas that had already been thoroughly explored, I decided that my investigation would provide the greatest value by concentrating on the Ministry of Long-Term Care’s inspections-related activity during the initial stages of the pandemic, and improvements that have been made since then. We focused on identifying further systemic changes and improvements that are necessary to ensure Ontario's long-term care sector is prepared for the next pandemic or similar health crisis.

8 Ombudsman staff sifted through more than 1.2 million documents and conducted 91 interviews for this investigation. What we uncovered was an oversight system that was strained before the pandemic, and proved to be wholly incapable and unprepared to handle the additional stresses posed by COVID-19. When the pandemic hit, the Ministry’s oversight mechanisms largely collapsed, with one Ministry employee describing it as “a complete system breakdown.”

9 During the critical initial weeks of the first wave, the Ministry’s Inspections Branch, which is responsible for receiving and inspecting complaints about long-term care homes, simply stopped conducting on-site inspections. For a seven-week period from mid-March to early May 2020, there was no independent on-site verification of the conditions in long-term care homes. The Inspections Branch did not clearly communicate its decision to stop on-site inspections to other areas of the government, long-term care homes, complainants or the public. Few knew that this oversight mechanism had fallen apart. In one area of the province, no on-site inspections occurred for three straight months.

10 Inspections stopped because the Ministry had no plan for inspectors to safely continue their work during a pandemic. The Branch did not have a supply of personal protective equipment, and inspectors were not trained on infection prevention and control. Once inspections resumed, and for much of the first wave, only inspectors who volunteered were sent to homes experiencing COVID outbreaks. Consequently, some areas of the province had as few as three or four inspectors to conduct on-site work, when there would normally be 20 to 25.

11 Rather than conducting inspections, the inspectors – who would typically be responsible for enforcing compliance with long-term care legislation – were tasked with “supporting and monitoring” long-term care homes through periodic telephone calls. Some homes refused to participate in these calls. At an already chaotic time, this switch to a new role and approach was confusing for long-term care homes and inspectors alike. In many cases, it also duplicated a function undertaken by other organizations.

12 The Inspections Branch was quickly overwhelmed by an unprecedented volume of complaints and questions from concerned families and caregivers. The Ministry did not adequately assess these complaints and conduct inspections when necessary. Instead, it primarily relied on inspectors to convey “key messages” over the phone and rebranded its complaints line as the “Family Support and Action Line,” resulting in confusion and undermining the compliance function of the Branch.

13 The Ministry put little thought into how its standard triage risk system would assess COVID-related complaints, resulting in a failure to categorize serious allegations as “high-risk.” It also took a narrow approach to its mandate and we discovered that extremely serious COVID-related issues – such as infection prevention and control or personal protective equipment usage – were not inspected in a timely manner, or at all.

14 In one case we reviewed, Peter[2] complained to the Ministry four times between April 6 and May 5, 2020, about disturbing conditions in his mother’s long-term care home. None of his concerns were inspected until October 2020, many months after his mother had already died from COVID. In total, 53 residents died at that same long-term care home during the first wave.

15 In another case, Gemma complained to the Ministry in April 2020 that her parents’ long-term care home was “severely short” on personal support workers. Gemma said residents were not being fed, cleaned or given their medications. One of Gemma’s parents had died of COVID, and the other was sick with the virus. A Ministry inspector "reassured” Gemma over the phone and then closed the file without taking any action. Thirty-three residents died at that long-term care home during the first wave. It’s impossible to know what might have happened if the Ministry inspectors had diligently followed up on complaints like Peter’s and Gemma’s when they were received.

16 In addition to its complaint-based inspections, the Inspections Branch conducts inspections in response to critical incident reports received directly from long-term care homes. Long-term care homes are required by law to report “critical incidents”, which are defined by legislation and include outbreaks of a disease such as COVID-19. Before the pandemic, the Ministry rarely did anything with critical incident reports about disease outbreaks. When the pandemic struck, many homes facing COVID-19 outbreaks did not report them as required and the Inspections Branch largely ignored their failure to make these reports. The Inspections Branch also did little – often nothing – when homes did file reports about COVID-19 outbreaks. By failing to follow up on these critical incident reports, as well as with the homes that failed to file them, the Ministry lost a valuable opportunity to inspect and intervene in homes facing outbreaks before conditions further deteriorated.

17 Our investigation also found that the Ministry took limited steps to enforce compliance with legislative requirements during the first wave of the pandemic. The Ministry’s Inspections Branch has authority to impose a range of enforcement actions or “penalties” when inspectors find a home in contravention of the law. In many of the first-wave situations we reviewed, the Branch chose to take only minor enforcement action, even when faced with significant and repeated non-compliance that put residents at risk.

18 We saw many examples where inspectors used their considerable discretion to lower the default enforcement action that would otherwise apply, even in very serious situations and with little to no explanation. One of the most severe responses available to the Ministry – a mandatory management order where the Ministry must approve a new operator for a home – was rarely considered, and there were no clear criteria guiding its use. In many cases, homes were instead permitted to enter into voluntary management contracts, which do not allow for the same level of Ministry control or oversight.

19 Even in situations where the Branch took enforcement action and required homes to comply with the legislation, homes were generally given many months to fix serious issues related to resident care and safety. We reviewed one instance where an inspector found that a long-term care home was not complying with legislated infection prevention and control requirements. The inspector determined that this was causing “immediate harm” to residents, and that the issue was “widespread” in the home – the highest categories of “severity” and “scope” associated with legislative contraventions. The inspector also noted that the home had a recent history of previous non-compliance on the same issue. The Ministry’s own internal procedures directed that in such circumstances, it should revoke the home’s licence and put an interim manager in place as the home is wound down. Instead of taking these actions, the Ministry issued a compliance order, which is a lower-level enforcement action, and gave the home three months to comply.

20 To foster transparency and accountability, the Ministry’s enforcement actions and inspection results are documented in public inspection reports. However, for more than two months during the first wave, the Inspections Branch stopped issuing any inspection reports, even for completed inspections that pre-dated the pandemic. Even when reports were released, we observed that they were often unduly lengthy, dense with acronyms, and poorly organized. Key information of interest was buried in different sections of the reports, making it difficult to navigate. In addition, the Ministry often combined totally separate complaints into one report. All of these practices made it very difficult for the public to identify whether a home had complied with orders made following an inspection.

21 Some will say that this is simply a snapshot in time, and that vast improvements have been made since then. To be sure, since the pandemic’s first wave, and as a result of recommendations made by other bodies, there have been some changes to the Ministry of Long-Term Care’s practices and to the legislation governing long-term care homes. In April 2022, the Fixing Long-Term Care Act came into force. It provides for new enforcement options. A new “investigations unit” is under development, which will focus on prosecuting the most serious contraventions. The legislation also requires long-term care homes to be better prepared for future pandemics, with numerous new requirements related to infection prevention and control practices, training, visitation policies, emergency planning, and staffing.

22 Beyond these legislative changes, the Inspections Branch has also taken steps to better prepare itself to respond to a future pandemic. It has also committed to conducting periodic, proactive inspections at each long-term care home, and the government has increased its staffing levels to handle this increased workload.

23 Nevertheless, it is crucial that the Ministry fully understand and learn from the failure of the Inspections Branch to adequately and quickly respond to the emergency that arose in the long-term care sector in March 2020. Nearly 80,000 vulnerable long-term care residents rely on the Ministry of Long-Term Care’s oversight to ensure their homes are safe and secure. Tragically, it was unprepared and unable to ensure the safety of long-term care residents and staff during the pandemic’s first wave. It is my opinion that this was unreasonable, unjust, and wrong under sections 21(1)(b) and (d) of the Ombudsman Act.[3]

24 While the Ministry has already taken some steps to better prepare itself for the next emergency, the Inspections Branch must be ready to fulfill its mandate, no matter the circumstances. I have made 76 recommendations in this report. Of these, 72 are directed to the Ministry, two call on the Government of Ontario to support the Ministry in carrying out its legislative responsibilities, and two urge the Ministry and Government to work together to ensure the Ministry has sufficient inspectors and staff going forward. My report does not focus on or make recommendations to the Ministry of Health, which has been the subject of other reviews that resulted in numerous findings and recommendations.

25 Experts warn us that there will eventually be another pandemic. Evidence is building that climate change, combined with our ever-greater encroachment into wildlife habitat, is fuelling the risk of viruses spilling from animals into humans. “There will be another pandemic. Like death and taxes, it’s an absolute certainty,” says Dr. Allison McGeer, an infectious disease specialist and professor of laboratory medicine and pathobiology at the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health.[4]

26 We likely don’t have years to wait until the next pandemic. As Professor Jacob Lemieux from Harvard Medical School has noted, “we are seeing pandemics emerge frequently, not once in a lifetime, but in fact every few years, and we need to start preparing.”[5] Policy makers must demonstrate leadership and unity to combat future public health threats.The people of Ontario should be able to count on their public services to learn lessons from our experience with COVID-19 and be adequately prepared for the next threat to our collective health.

27 I am hopeful that these evidence-based recommendations, aimed at building on changes already in progress and enhancing pandemic preparedness in the inspection regime for long term care homes, will ensure that the Ministry is able to effectively meet its vital oversight responsibility during the next health crisis.

A Tragedy of Epidemic Proportions

28 The effects of the multi-year COVID-19 pandemic on Ontario’s long-term care sector have been severe and deadly. Although long-term care residents represent a tiny fraction of Ontario’s population, they account for nearly one-third of the province’s COVID death toll.

29 The first wave of the virus had a devastating impact on the long-term care sector, arriving at a time before vaccines were available and when personal protective equipment supplies and infection prevention and control expertise were hard to find. Some 1,937 COVID-related deaths occurred in the sector during the first wave, from January 15, 2020 to August 2, 2020. The vast majority of the other COVID-related deaths in the sector arose during the pandemic’s longer second wave, from August 2020 until February 2021. The availability of vaccines beginning in December 2020 was credited with substantially reducing the incidence of serious illness and death in long-term care residents thereafter.[6]

30 The impact of the pandemic was inconsistent across individual long-term care homes. For example, the 233-bed Orchard Villa home in Pickering experienced 70 resident deaths due to COVID. Meanwhile, other homes experienced no large outbreaks and few deaths.

31 The arrival of COVID-19 in Ontario evoked an unprecedented response. At times, precautionary measures in the long-term care sector came at the price of the individual rights of residents, including to receive visitors.[7] For instance, on March 13, 2020, Ontario’s Chief Medical Officer of Health strongly recommended that all long-term care homes allow visitors only for residents who were very ill or nearing the end of their life.[8] A few weeks later, the Chief Medical Officer required that long-term care homes “be closed for visitors, except for essential visitors.”[9] Family and volunteers who provided care services required to maintain residents’ health were later described as “essential visitors.” This restriction on visits remained in place for a long time, and deprived many residents of a significant source of family support. As one resident told us:

“…my world change[d]. I became a non-citizen…without the ability to make choices and decisions on how I live my life.”

32 Compounding the isolation were restrictions on residents’ movements within the homes. Many were mostly confined to their rooms, further reducing their opportunities for human contact. One resident told us it felt like being “in jail.” She added:

“I think the worst thing – and I’m sure I speak for a lot of residents – was the fact that we missed our families so much. That to me was the worst thing of the whole pandemic… I missed my family.”

33 The mandatory restrictions were also acutely felt by families and friends of residents. Prior to the pandemic, they could not only visit with residents to provide care and support, but observe their living conditions firsthand and report any concerns about their care to management and the Ministry. When they were shut out of the homes, an important connection with residents was lost, as well as a valuable source of information about the adequacy of care.

34 Many homes also suffered from staffing issues during the pandemic, and the absence of support from family and other caregivers increased the difficulties caused by those shortages. We heard of multiple homes during the first wave where more than 80% of staff tested positive for the virus at the same time, leaving most unable to work. We heard many examples of the impact this had on residents. In April 2020, according to a Ministry of Long-Term Care inspector, a staff person at the Orchard Villa home in Pickering called the Ministry to report that “…there is no staff to feed and care for residents, and that living conditions are like hell.” Ministry inspectors did not enter homes during the peak of the first wave, so there was little external oversight as homes struggled to meet residents’ basic needs.

35 The first wave also severely affected long-term care staff on the front lines in individual homes. Canadian Armed Forces personnel who were called in to help described the workers they supported at one home as overworked and burned out, and noted many had “not seen their families for weeks.”

36 Officials from Canadian Union of Public Employees Ontario told us many of their Ontario members working in the homes were physically and emotionally exhausted during the first wave. They said some were given the task of putting residents’ bodies into body bags, far from their typical duties, and that these staff would feel the psychological impact “for years to come.” A senior official at the Ontario Personal Support Workers’ Association had similar comments, comparing long-term care homes during the first wave to a “battlefield.” Although my Office does not oversee the living or working conditions in individual long-term care homes, the horrendous conditions experienced by many long-term care residents and workers provides important context for assessing the role played by the Ministry of Long-Term Care’s Inspections Branch during the first wave.

Investigation Scope and Process

37 In June 2020, I informed the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Long-Term Care that my Office would investigate the adequacy of their oversight of the long-term care sector during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. The investigation was launched on my own initiative and was to examine how the two ministries ensured the safety of long-term care residents and staff. I made this decision after the publication of a letter[10] by the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) personnel that provided disturbing details about the conditions in long-term care homes that had received CAF assistance. I was also disturbed by the growing number of COVID outbreaks and COVID-related deaths in long-term care homes across the province, as well as an increase in complaints to my Office.

38 Although other reviews were underway or had been announced, I was confident that my Office’s privileged relationship with Ontarians and the singular perspective we are afforded by hearing directly from people and working to resolve their individual complaints would enable us to make a unique and valuable contribution to finding solutions.

39 A previous investigation by this Office in 2008 regarding the province’s oversight of the long-term care sector identified several issues, which were set out in a letter tabled with the Ontario Legislature in November 2010.[11] These issues were considered by the then-Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care as it made numerous legislative and operational changes to modernize the sector.[12]

A challenging investigation

40 When I announced this investigation in June 2020, few could have known the ways in which COVID would affect day-to-day life over the coming years. As those impacts became clearer, and as other organizations undertook their own investigations and reviews, I decided that my investigation would produce the greatest impact by focusing on the Ministry of Long-Term Care’s inspections-related activity during the initial stages of the pandemic, with a view to recommending improvements that will strengthen oversight for the future and ensure that the Ministry and Ontario’s long-term care homes are better prepared for the next pandemic. Other matters related to COVID in the long-term care sector, such as pandemic planning, responses to subsequent waves of infection, licensing of homes, and steps taken by the Ministry of Health, have been investigated and reported on by other organizations.[13]

41 The Special Ombudsman Response Team (SORT) led this investigation, supported by other staff from our Generalist Early Resolution and Investigations teams, as well as Legal Services staff.

42 In response to our requests, we received more than 1.2 million documents – mostly emails and their attachments. We conducted 91 interviews with staff from the ministries of Long-term Care and Health, other government officials, long-term care home administrators, and other relevant stakeholders. We also obtained information from the Canadian Armed Forces. In addition, we met virtually with officials from the Ministry of Long-Term Care and the Ministry of Health on several occasions to obtain information about their operations, and to receive updates on changes to legislation, policies and other relevant initiatives.

43 It was difficult to conduct such a large and complex investigation during the pandemic. This was one of the first Ombudsman investigations conducted while staff worked remotely, and it was necessary to put new information technology infrastructure in place to allow staff to effectively and confidentially carry out their work. While remote work is now second nature to many, in June 2020 it was a major departure from our typical investigative approach.

44 Our investigation was also affected by the workload of staff at the ministries we were investigating. Understandably, many were preoccupied with responding to the ongoing impact of the pandemic, especially as it became clear that the second wave of the pandemic would be even more devastating than the first. We also heard that requests relating to other reviews and investigations, including those of the Auditor General, Long-term Care COVID-19 Commission, and Patient Ombudsman, hampered staff’s capacity to respond to our requests. We also struggled to interview several key individuals due to leaves of absence, retirements, other urgent priorities, and numerous personnel changes.

45 Cognizant of the challenges facing public sector officials, we worked collaboratively to determine how and when documents would be provided and interviews scheduled. For example, we allowed the ministries to provide documentation in instalments – a departure from our usual process. We also allowed interviewees to reschedule their time with us if they were urgently needed elsewhere.

46 This approach, unfortunately, dramatically affected the timeliness of the information we received. For example, it took Ministry officials more than three months to answer our request for basic information about inspectors, which we needed in order to decide which inspectors to interview. When we finally received a response, it was too late to be useful in the investigation and did not offer us the details we had requested. It also took more than seven months for officials to begin sending us copies of certain Ministry inspection files that were key to our investigation.

47 Most concerning, the Ministry did not provide copies of all relevant emails and email attachments for more than a year. During this lengthy delay, we worked diligently with the Ministry and a third-party vendor it hired to provide detailed information about our request. When concerns were raised about the volume of emails that would be produced, we narrowed the date range and scope of our request. We were told that this would yield about 67,000 emails – a large, but manageable number. What we ultimately received was very different – a mass of over 1 million emails with no organization by subject-matter. More than 300,000 documents were unsearchable PDFs, provided without context or other form of organization. My Office’s Information Technology team was able to develop some solutions, but given the sheer volume of information, it was not possible for investigators to read every email and document. Instead, we relied on filters, sorting, and targeted searches to select documents most likely to be relevant to our investigation.

48 These delays, and the volume of information produced, impacted our ability to conduct interviews in a timely manner, since, as a best practice, we try to review the key documents relevant to witnesses before we speak with them.

49 It was also difficult to confirm whether the Ministry provided us with all the relevant information we had requested. The Ministry withheld or redacted more than 38,000 documents because they contained information that the Ministry said did not need to be disclosed – e.g., due to solicitor-client privilege. It is common for organizations to assert this type of privilege during Ombudsman investigations, but it usually does not apply to a large number of documents, and we normally receive a detailed explanation as to why each document is being withheld. In this case, we only received a spreadsheet listing basic details about the 38,000 records, and there was little explanation for why each withheld document was privileged. When we asked a senior Ministry official to clarify how the government determined which records were subject to privilege, we were told that they relied on specific software to do an initial search, with Ministry lawyers “auditing” the search results. It was impossible for our staff to determine if documents had been properly withheld.

50 Despite these obstacles, we appreciate the co-operation we received from the Ministries and acknowledge the serious challenges they faced in trying to respond to the pandemic itself, our investigation, and several other reviews and investigations.

51 This investigation required a tremendous amount of planning and preparation. The investigative process – particularly interviewing witnesses and obtaining documentary evidence – was hampered considerably by the state of public health, staffing levels and having to conduct much of the work virtually. Nonetheless, it was imperative that we conduct a thorough and rigorous investigation that took account of the situation from a variety of perspectives.

52 Moreover, our Office was not at its full staffing complement during this investigation, which also affected timelines. Two significant expansions of the Ombudsman’s mandate (in 2016 and 2019) not only greatly increased the scope of our jurisdiction but also resulted in higher caseloads. Although we have added staff and continue to do so, during the period of this investigation our human resources unit lacked the capacity to get us to a full staffing complement and optimize our operations.

Cases received

53 This investigation was launched on my own motion. However, my Office has broad authority to review complaints about the administrative conduct of the Ministry of Long-Term Care, as well as the Patient Ombudsman, who has a mandate to directly review complaints about long-term care homes and other health services. My Office’s mandate does not include complaints about individual long-term care homes, their staff, or public health units.

54 We received 269 cases (complaints and inquiries) related to the issues under investigation. Most of these were received at the height of the pandemic’s first wave and related to concerns about the government’s handling of the pandemic in the long-term care sector. Many came from family members of long-term care residents and raised general concerns about the government’s planning and early response, as well as specific issues related to personal protective equipment, COVID testing, infection prevention and control, and restrictions on visitors. We also received a significant volume of cases from long-term care home staff, family councils and other stakeholders. Some of these were about how the Ministry communicated important pandemic-related information to Francophones; these cases were dealt with by my Office’s French Language Services Unit.

55 Many of the cases we received related to issues in individual long-term care homes, and our Early Resolution Officers referred them to the Ministry of Long-Term Care’s Inspections Branch, the Patient Ombudsman or to other resources, such as the Advocacy Centre for the Elderly.[14] Many others raised concerns about the Ministry’s inspection and complaints process, including issues such as delayed responses, inadequate investigations of complaints, poor communication, and disagreement with the Ministry’s enforcement actions or lack thereof. Ombudsman staff worked to resolve these individual issues, while the evidence they gathered helped guide our investigation.

56 We received very few complaints directly from long-term care residents, and while it is impossible to know exactly why, there are many potential reasons. Most residents require extensive help with daily activities, including the use of a telephone or computer. Many experience some form of cognitive impairment or neurological disease that may make it difficult or impossible to contact my Office. To assist in understanding the perspective of residents in such situations, our investigators spoke with long-term care residents and other representatives involved with the Ontario Association of Residents’ Councils and Family Councils Ontario.

57 In addition to receiving and resolving individual complaints, my Office’s French Language Services Unit also worked to ensure that the needs and interests of Francophones were considered by the Long-Term Care COVID-19 Commission. Following this input, the Commission invited Francophones to appear before it to assist in analyzing the specific issues affecting them and identifying solutions. In its report, the Commission recognized that Francophone long-term care residents must receive culturally and linguistically appropriate care and services, and made two recommendations related to French language services.[15]

Long-term Care in Ontario

58 There are more than 600 long-term care homes in Ontario, comprising nearly 80,000 resident beds. These homes are places where adults can receive help with most or all daily activities and access to 24-hour nursing and personal care.[16] Long-term care residents are some of the most vulnerable people in Ontario. The vast majority of residents need extensive help with tasks such as getting out of bed, eating, or toileting, and experience some form of cognitive impairment or neurological disease.

59 The long-term care home sector is large, employing more than 100,000 people in the province. Around 60% are personal support workers, who help residents with bathing, dressing, eating, and moving around the home. Another 25% are registered nurses or registered practical nurses.[17] Doctors and other medical professionals also provide care to residents.

60 Through most of the pandemic, the Long-Term Care Homes Act, 2007 and Ontario Regulation 79/10 governed the provision of long-term care.[18] In April 2022, these laws were repealed and new legislation, the Fixing Long-Term Care Act, 2021 came into force.[19] Both Acts establish a similar structure for the provision of long-term care services and Ministry oversight.

Ministry of Long-Term Care

61 The Ministry of Long-Term Care is responsible for licensing long-term care homes, receiving complaints, conducting compliance inspections, and taking enforcement action if a home is not complying with legal requirements.

62 As of March 2020, the Ministry’s Operations Division handled inspections, enforcement and licensing. Within this division, the Inspections Branch is responsible for inspecting homes to ensure they are complying with legislation and any Ministry directives. If a long-term care home is not in compliance, the Branch decides what enforcement action to take.

63 Long-term care homes are owned by a range of entities, including municipalities, for-profit companies, and non-profit organizations. Each owner and long-term care home must be licensed by the Ministry of Long-Term Care.[20] The Ministry has broad authority when licensing homes and can add conditions to a home’s licence, amend a licence, and revoke a licence completely, if necessary. At the start of the pandemic, the Licensing, Policy and Development Branch was responsible for this function, although in June 2020 it shifted to the Long-Term Care Capital Development division.

Other sources of oversight

64 In addition to the Ministry of Long-Term Care, other organizations oversee long-term care homes, including the Ministry of Health, local public health units, and the Patient Ombudsman.

Ministry of Health

65 Among many other mandates, the Ministry of Health is responsible for the planning and co-ordination of emergency response for the whole health system, including the long-term care sector. This role is set out and guided by the Emergency Management and Civil Protection Act, and Ontario Regulation 380/04.[21] While this legislation gives this responsibility to the Ministry of Health alone, we were told that in practice it carries out its responsibility in co-ordination with the Ministry of Long-Term Care.

66 The Office of the Chief Medical Officer of Health is part of the Ministry of Health, and the Health Services Emergency Management Branch reports to that office. This branch is responsible for the policy, programming, planning and co-ordination work for emergencies across the health care sector, including in long-term care homes.

Patient Ombudsman

67 The Patient Ombudsman is responsible for taking complaints about the care and health care experience of residents in long-term care homes, patients in hospitals, and individuals receiving services from Home and Community Care Support Services.[22] Like our Office, it is considered the “recourse of last resort.” The Patient Ombudsman attempts to resolve long-term care home complaints through mediation and negotiation, or through investigation if necessary.[23] It has released three “special reports” during the pandemic on complaints about long-term care homes.[24]

Local public health units

68 Ontario is divided into 34 geographic areas called public health units.[25] Each is led by a local medical officer of health who reports to the local board of health, and is responsible for taking action to safeguard the public’s health at a local level. Local medical officers of health and their public health units assist in identifying and managing outbreaks of disease in long-term care homes and provide proactive outreach and education. Public health units can also inspect infection prevention and control practices in long-term care homes, although most do not do this proactively.

69 If warranted, local medical officers can issue orders to long-term care homes under the Health Protection and Promotion Act, requiring them to take (or refrain from taking) certain actions. During the first wave of the pandemic, several public health units used this power to impose conditions on long-term care homes that were struggling to cope with outbreaks.

70 The Health Protection and Promotion Act requires long-term care homes to report cases of certain diseases to their local public health unit as soon as possible, and since January 22, 2020, COVID has been a reportable disease.[26] The Ministry of Health created a guide called the Institutional/Facility Outbreak Management Protocol, which sets out what public health units should do when responding to reported outbreaks of disease in certain settings, including long-term care homes.[27] The guide specifies that public health units “assist” facilities, while the homes themselves retain responsibility for managing outbreaks.[28]

71 In the first wave of COVID, there was little guidance for public health units about what role they were supposed to play during a widespread pandemic, especially in the context of long-term care homes. The government’s 2013 Ontario Health Plan for an Influenza Pandemic provided some general guidance for what the units would do, such as collecting and analyzing local data, leading local immunization efforts, and developing and issuing orders.[29] However, there were no specific sections related to public health units in the context of long-term care, and we heard that different public health units took differing approaches during the first wave of the pandemic.

72 My Office has no authority to review complaints about public health units, and in 2020-21, we had to turn away 87 cases about them. This included issues related to COVID testing, contact tracing, mask and social distancing guidelines, local orders, and access to vaccines. I flagged this serious issue in my 2020-21 Annual Report, noting that:

Public health units have been central to Ontarians’ experience of the pandemic, responsible for everything from playground closures to mask mandates to vaccination operations. Their work is crucially important and their decisions collectively affect millions. And yet they operate without oversight: They are exempt from the jurisdiction of my Office, and that of the Ministry of Health’s Patient Ombudsman.[30]

73 At that time, I encouraged the province to implement independent oversight of public health units. In 2021-2022, we received another 137 cases about public health units, which we were unable to address.[31]

A Focus of Inquiry

74 Several oversight bodies with varying mandates have conducted reviews and made recommendations related to the long-term care sector and the province’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Substantial expertise, time and money went into the important work of these other organizations, and my own investigation is meant to build upon, not duplicate, their findings and recommendations.

Gillese Inquiry

75 Between 2007 and 2016, registered nurse Elizabeth Wettlaufer intentionally gave insulin overdoses to a series of long-term care home residents. Her actions killed eight people, and seriously harmed at least six others. She later confessed, resulting in her prosecution and conviction.[32]

76 After the trial, the Ontario government asked the Honourable Justice Gillese to lead a public inquiry into the safety and security of residents in Ontario’s long-term care homes. The inquiry was held between 2017 and 2019, and Justice Gillese’s final report was released on July 31, 2019.[33]

77 The report made three central findings: That no one would have discovered what Elizabeth Wettlaufer did had she not confessed; that the events were the result of systemic vulnerabilities in the long-term care system; and that the long-term care sector is “strained but not broken,” with long-term care homes under pressure because they have limited resources.[34]

78 Among the report’s many findings and recommendations was a call for the then-Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care to create a dedicated unit to support long-term care homes in achieving compliance with the law.[35] It also made a series of recommendations around the reporting of serious incidents to the Ministry, and about how the Ministry should inspect the highest-risk issues. Specifically, it called on the Ministry to tweak its performance assessment methodology to give more weight to “high-risk” issues, which should be inspected as quickly as possible to mitigate the risk of harm to residents.[36] It asked the Ministry to use performance data to help it determine how quickly to inspect issues, and to act when the data shows a home is struggling to provide a safe and secure environment.[37] It further asked the Ministry to educate the public about which incidents must be reported.[38]

79 The Gillese report also recommended the Ministry carry out a study to determine adequate staffing levels for homes.[39] This study was done largely during the pandemic’s first wave and was tabled in July 2020. The resulting report recommended that each resident receive a minimum daily average of four hours of direct care and called on the government to provide additional funding for homes to achieve that goal.[40] This latter report recommended that the government create guidelines on staffing ratios and mix and called for better recognition for the role of personal support workers and greater use of nurse practitioners. It also made numerous recommendations about working conditions for long-term care staff. Some of the recommendations made by this study have been incorporated into the Fixing Long-Term Care Act, 2021, which came into force in April 2022.

Independent Long-Term Care COVID-19 Commission

80 The largest and most comprehensive review of COVID-19 in the long-term care sector was conducted by the Independent Long-Term Care COVID-19 Commission. The Commission was announced in May 2020 and formed on July 29 that year, with a mandate to investigate how and why COVID-19 spread in long-term care homes, what was done to prevent the spread, and the impact of key elements of the existing system on the spread.[41] The Commission issued interim reports in October and December 2020, and its final report was published in April 2021.

81 The October 2020 interim report provided the government with early recommendations that it could implement immediately as a growing second wave of the virus quickly overtook long-term care homes.[42] Among other things, it called for improved staffing and asked the government to help the homes build better relationships with local hospitals and public health units.[43] It suggested that every home have a dedicated infection prevention and control lead, and that Ministry inspectors should ensure that homes were following infection, prevention and control procedures properly.[44]

82 The Commission released its second interim report in December 2020 as the pandemic continued to worsen. Among its recommendations were a requirement that homes report and publicly post more data, including staffing levels and supplies of personal protective equipment.[45] It also called on the Ministry of Long-Term Care to restart its proactive resident quality inspections (RQIs) at all homes, and include a review of infection prevention and control practices as part of all reactive inspections. To operationalize these inspections, it recommended that the government give the Ministry enough money to hire and train inspectors to carry out an RQI at every home every year. It further recommended that the Ministry respond faster when it issues orders for IPAC and “plan of care” issues.[46] Additionally, it urged the Ministry of Long-Term Care, the Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development and public health units to co-ordinate their inspections and share information.[47]

83 The Commission published its final report in April 2021. At over 300 pages, it provided a detailed review of the state of the long-term care sector before and during the pandemic (to that point), and the many factors that affected the ability of homes to keep residents safe from COVID. It made 85 recommendations.[48]

84 Quoting extensively from the experiences of residents, family members, caregivers and long-term care home staff, the Commission said each group “suffered terribly” during the pandemic. Residents were “neglected, scared, alone and cut off from those they love and depend on.” Meanwhile, the long-term care home staff who were able to keep working watched their residents die – and then sometimes had to prepare the bodies after death, leaving many traumatized.[49]

85 The Commission made strong comments on the government’s lack of planning for a pandemic like COVID-19. It noted that for years, the province had implemented important recommendations from previous reports to prepare for a future pandemic – including several studies arising from the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak.[50] But over time, the province “lost the will to make pandemic preparedness a priority,” the Commission said, even though it was foreseeable and inevitable that a deadly pathogen would someday sweep the world.[51] According to the Commission’s report, when COVID emerged, the province didn’t have an up-to-date pandemic plan. The existing plan focused on influenza, had not been updated since 2013, and contained no specific guidance for the long-term care sector. Instead, the province had invested years of work in a new “ready and resilient health system” plan, which was not ready when COVID arrived.[52] The Commission said planning for a pandemic must be a constant priority, and called on the government to finalize its plan, make it public, and include specific guidance for long-term care. It also stressed that every long-term care home should have its own pandemic plan.[53]

86 The Commission’s report also discussed the adequacy of the province’s emergency supplies at length. It notes that in 2017, the province discovered that most of its stockpile of emergency health supplies had expired after being amassed in the wake of the SARS outbreak. The province ordered the destruction of 90% of the stockpile and spent three years deliberating on whether and how to replace it.[54] In addition, there was no requirement for long-term care homes to have a specific supply of personal protective equipment. By the time COVID arrived, the province’s supply of usable equipment had been significantly depleted and there was no way of knowing the state of supplies at individual long-term care homes. The Commission recommended that the government enact legislation regarding the provincial stockpile, and put the Chief Medical Officer of Health in charge of it. It also called on the government to actively manage its emergency supplies and ensure long-term care homes have priority access.[55]

87 The Commission also found that uncertainty around roles and responsibilities made the situation even more precarious. When the pandemic began, a large number of organizations were merging into the new Ontario Health agency, leaving some key responsibilities unfilled or unclear. One agency that should have been central to the pandemic response – Public Health Ontario – was underfunded and out of the loop. Further, the recent creation of a separate Ministry of Long-Term Care meant that its responsibilities hadn’t been fully delineated, leaving the new ministry “fighting to be heard.”[56]

88 The Commission’s report also found that when the virus arrived, the government didn’t have a command structure ready and was making up its response as it went along. It said officials were confused about who was doing what, and who was actually in charge. Key public health decisions were not made by experts and there was poor communication between the different “tables” tasked with pandemic response. Notably, the government didn’t create a response table for long-term care until late-April 2020.[57]

89 With respect to the long-term care sector, the Commission found that homes were highly vulnerable when the pandemic began because successive governments had failed to tackle longstanding problems, including chronic underfunding, severe staff shortages, outdated infrastructure, and inadequate oversight. To compound these issues, the homes were poorly connected to the rest of the health system. After SARS, long-term care homes lost their links with hospitals because they were supposed to get their own infection prevention and control (IPAC) experts. But the role of internal IPAC lead within homes often fell to an “otherwise busy nurse” who was not primarily devoted to the task.[58] The Commission recommended that the government require homes to have their own full-time IPAC practitioners, better training around IPAC, and formal links with the rest of the health system.[59]

90 The Commission wrote at length about the impact of inadequate staffing in homes. It found existing staffing levels were insufficient, and constant shortages, excessive workloads, high turnover rates, and heavy reliance on part-time workers are common in the sector. Specific to COVID, the Commission observed that the government was too slow to limit long-term care home staff to working at one location to prevent the spread of disease between homes, and the government had no plan to replace workers who stayed away when outbreaks struck, causing “many residents to suffer from malnutrition and dehydration, sometimes with fatal consequences.”[60] The Commission called on the government to address staffing shortages, and to build a bigger long-term care workforce with the necessary mix of skills.[61]

91 Regarding inspections, the Commission found that the “almost total elimination” of the proactive resident quality inspections (RQIs) before the pandemic “left the Ministry of Long-Term Care with a very limited picture of the state of long-term care homes, and virtually no idea of a home’s IPAC and emergency preparedness when the pandemic began.”[62] It described the Inspections Branch as “missing from action and invisible” during the pandemic, lacking both direction and inspector capacity during the first wave.[63] The Commission recommended the Ministry conduct more timely inspections of infection prevention and control and carry out a proactive inspection of each home annually. It also called on the government to provide the Ministry enough funding for the necessary inspectors.[64]

92 The Commission specifically commented on the Ministry’s lack of enforcement when homes failed to comply with the law. It noted the Ministry of Long-Term Care rarely used Director’s Orders and fines, and instead took low-level actions for most situations of non-compliance. It said the absence of strong action likely explained the lack of urgency among long-term care operators to comply with the law, and called on the Ministry to take “proportionate and escalating consequences” for non-compliance.[65]

93 Overall, the Commission found that the government “failed to prioritize long-term care before the disease had already gained a fatal foothold in homes.”[66] Its report noted the government did not heed the experiences of other jurisdictions, even though by mid-March 2020, many other jurisdictions had already seen high death rates in long-term care from COVID. Rather, it observed, the government continued to tell the public the risk posed by COVID was “low,” even after officials agreed in private that spread was inevitable.[67]

94 After the report’s release, the Minister of Long-Term Care committed to reviewing the final recommendations carefully in the government’s ongoing efforts to fix the systemic issues facing Ontario's long-term care sector. The Ministry has since implemented a number of the Commission’s recommendations. For instance, in late November 2021, it restarted proactive inspections, which are now called “proactive compliance inspections.”

Office of the Auditor General of Ontario

95 The Auditor General has also issued several reports regarding the province’s oversight of long-term care homes.

2015 special report and 2017 follow-up

96 In a 2015 special report regarding long-term care oversight, the Auditor General found that the then-Ministry of Health and Long-term Care was taking too long to inspect high-risk complaints and critical incidents in long-term care homes.[68] The report said this was because the Ministry had focused its resources on annual, proactive resident quality inspections, which caused a growing backlog for complaint and critical incident-driven inspections. It also found the Ministry was not appropriately prioritizing its proactive inspections according to the risk each home presented.[69]

97 With respect to the inspections it did conduct, the Auditor General noted that the Ministry gave homes inconsistent timelines to implement its orders, and then often failed to re-inspect homes within the timeframe it had selected. The timeliness and effectiveness of the Ministry’s inspections varied significantly across the province.[70] The 2015 report specifically called on the Ministry to take stronger action to address repeated non-compliance in certain long-term care homes.[71]

98 In 2017, the Auditor General released an update on this investigation, indicating the Ministry had only made patchy progress on the issues identified in 2015. This report said the Ministry had developed a shorter version of its comprehensive resident quality inspection (RQI), and would only conduct a full RQI at each low-risk home every three years, instead of annually. The Ministry was referring more cases of repeated non-compliance to the Director, and planned to introduce new enforcement measures through legislative change. However, the Auditor General found the Ministry still had a large backlog of complaints and critical incidents that needed inspection.[72]

Special COVID-19 audit

99 In response to the COVID-19 crisis, the Auditor General conducted a special audit into the province’s response and released her findings as six separate “chapters” through 2020 and 2021.[73] One of those chapters – Chapter Five: Pandemic Readiness and Response in Long-Term Care – specifically addressed the impact on the long-term care sector. It was released in April 2021 and covered the period from January 2020 to December 2020.[74]

100 The chapter identified three central issues that made it difficult for the government to respond to the needs of long-term care homes. First, it found that the province had taken insufficient action to implement the many observations and recommendations made after SARS to ensure Ontario was better prepared for “next time.” Second, the government generally hadn’t addressed systemic weaknesses in the delivery of long-term care. Third, the lack of integration between long-term care and the rest of the health care sector, compounded by an ongoing reorganization of the sector, left long-term care homes without access to infection prevention and control expertise at the start of the pandemic.[75]

101 The chapter also outlined a series of pre-existing concerns with the Ministry of Long-Term Care’s Inspections Branch that left homes more vulnerable to disease. It stated that the long-term care legislation wasn’t strong or specific enough to enable inspectors to check whether homes had good infection prevention and control programs, and the vast majority of the inspectors didn’t have enough IPAC knowledge to do so. It noted the Ministry had historically inspected very few outbreaks of disease in long-term care, and that after proactive inspections were discontinued, few IPAC issues were found during inspections. It also observed the Ministry’s decision to pause resident quality inspections was contrary to the Auditor General’s 2015 audit recommendations and compromised the Ministry’s oversight of homes.[76]

102 The Auditor General also identified many problems with the Ministry’s Inspections Branch once the pandemic arrived, including the Branch’s failure to conduct on-site inspections for an extended period. She noted that it mainly used low-level enforcement actions, even in the face of repeated non-compliance with the law.[77]

103 Another chapter of the Auditor General’s COVID-19 special report reviewed the government’s outbreak planning and decision-making for the health sector more broadly. It indicated the province hadn’t updated its pandemic plan since 2013 and found that those making key decisions were not public health experts, that Public Health Ontario had played a diminished role, and that the Chief Medical Officer of Health did not exercise his full authority. It stated that the government failed to follow the lessons from SARS, and that it characterized the risk of COVID as low despite the inevitability that it would spread. It also observed the province took too long to compel long-term care staff to wear masks and to prohibit long-term care staff from working across multiple sites.[78]

104 A further chapter, released in December 2021, reviewed the supply of personal protective equipment (PPE) in the province. The Auditor General noted that her office reported in 2017 that most PPE in the province’s stockpile had expired and the government was destroying it without replacing it. The chapter said the government’s efforts to centralize the PPE supply chain were not ready, and health care workers, including long-term care home staff, were not always properly protected with PPE.[79]

105 The other chapters of the Auditor General’s Special COVID-19 Report highlighted issues with testing, case management and contact tracing, expenditures and planning for non-health settings.[80]

Patient Ombudsman

106 The Patient Ombudsman has direct oversight of long-term care homes. On June 2, 2020, that office announced its first-ever systemic investigation, into the experiences of residents and caregivers in long-term care at the onset of the pandemic.[81] The Patient Ombudsman has issued three special reports setting out the types of complaints the office has received,[82] as well as the results of a survey of residents, family members and staff.[83]

107 The Patient Ombudsman’s first special report was released in October 2020 and summarized the most common complaints in long-term care during the first wave.[84] These included concerns about visitation restrictions and infection prevention and control, as well as communication issues. The report made some preliminary recommendations, including that every long-term care home should partner with an outside organization, such as a hospital, to obtain the necessary resources to respond to COVID outbreaks. The report also recommended all homes have a plan to manage significant staffing shortages, outbreaks and infection prevention and control matters. The Patient Ombudsman also urged the government to ensure “essential caregivers” could still visit and communicate with residents.

108 The Patient Ombudsman’s second special report was released in August 2021 and covered complaints from the second and third waves of COVID about long-term care, public hospitals and home and community care. The report offered an update on the most common long-term care complaints, and some examples of the stories his office heard from residents and caregivers. He recommended the government guarantee long-term care residents the right to receive visitors, and ensure that any restrictions on visits were necessary and risk-based. As well, he called for more supports for health care workers and said long-term care homes should have a plan in place to communicate significant policy changes that affect residents and caregivers.[85]

109 The Patient Ombudsman’s third special report was released in December 2021 and summarized the results of surveys of long-term care home residents, their loved ones and staff about their pandemic experiences. The report noted the effect of “chronic staffing shortages, as well as the impact of prolonged isolation and lack of stimulation on residents’ emotional health and well-being.”[86] It observed that many loved ones were still struggling to visit residents, and reiterated that balancing infection prevention and control measures with residents’ quality of life was a critical challenge.[87]

110 These reports by the Patient Ombudsman, the Auditor General, and the Independent Long-Term Care COVID-19 Commission made important contributions to understanding the impact of COVID-19 in Ontario and led to significant recommendations for improvements. Although my Office’s investigation focused on the same event, it did so from a unique perspective, shaped by our expertise in administrative fairness. We explored in great depth how the Ministry of Long-Term Care’s Inspections Branch responded to the crisis and how it addressed the serious concerns brought forth by long-term care home residents, their family members and other caregivers. In doing so, we were able to identify systemic issues that directly affected the adequacy and responsiveness of the Branch’s inspections and the remedial measures taken to address non-compliance by long-term care homes. The impact of systemic problems within the Branch was heightened during the pandemic’s first wave. However, many of the issues we discovered reflected pre-existing administrative flaws that transcended the pandemic. In addition, our investigation revealed significant new evidence about how the Ministry of Long-term Care’s Inspections Branch responded to the challenges of the pandemic’s first-wave, and it is important that this information be part of the public record and discourse.

The Inspections That Never Were

111 As other reports and investigations relating to COVID-19 have demonstrated, the long-term care sector has faced chronic challenges, which the pandemic magnified intensely. One of the Ministry of Long-Term Care’s greatest failings during the first COVID wave was its inability to mobilize its inspectors as successive long-term care homes succumbed to outbreaks. For an extended period, the Ministry’s oversight of the sector was essentially non-existent, as its primary tool for assessing the living conditions within Ontario’s long-term care homes – on-site inspections – was shelved.

The inspection landscape as COVID-19 arrived

112 The Ministry of Long-Term Care relies on inspections to determine whether a long-term care home is complying with its legislative obligations. Prior to the pandemic, the Inspections Branch typically conducted about 3,000 inspections annually in accordance with its authority under the Long-Term Care Homes Act, 2007.

113 Inspectors have broad powers. They can enter a long-term care home at any reasonable time without notice; examine premises, demand, view and copy records, question people, make recordings, remove evidence, call in outside experts, and obtain search warrants if necessary.[88]

114 The Ministry’s Inspections Branch is led by a Director, who has many specific responsibilities and powers set out in legislation. The Branch is further divided into seven regional service area offices, each of which has one Service Area Office Manager, two inspection managers, 22 to 25 inspector positions, as well as some administrative staff.[89] Four senior managers share oversight of the seven service area offices.

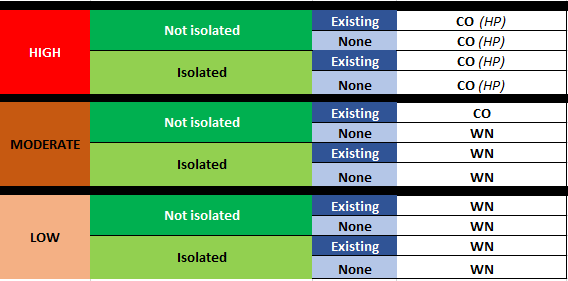

115 The Branch conducts inspections into complaints, critical incidents and open Ministry compliance orders. It can also conduct proactive inspections. Complaints and critical incidents are assessed and given a risk level from 1 to 4, with 4 representing the highest level of risk. Generally, the Branch inspects files with a triage risk level of 3, 3+, or 4. When the pandemic began in March 2020, the Branch was carrying out four types of inspections:

- Complaint inspections: These occur in response to specific complaints about homes filed by residents, their family, or others.

- Critical incident inspections: A “critical incident” is a specific type of event that a home is required by law to report to the Ministry. It includes significant outbreaks of disease.

- Follow-up inspections: These check whether the home has remedied issues that the Ministry previously ordered the home to fix.

- Service Area Office-initiated inspections: These give the Ministry authority to inspect any home on the Ministry’s own initiative.

116 Each home must be inspected at least once per year and inspections are typically unannounced.[90] In the past, the Branch also conducted resident quality inspections or RQIs. These were more comprehensive inspections that examined a standard list of items in the home. However, this type of inspection was resource-intensive and led to backlogs prior to the pandemic. The Branch switched to a risk-based inspection approach and completed its last pre-pandemic RQI in July 2019.

117 The Ministry records inspection findings and related enforcement actions in reports, which are shared with long-term care homes and posted with anonymized resident information on the Ministry’s “Reports on Long-Term Care Homes” website.[91] When the pandemic began, enforcement actions ranged from a written notification, which resulted in no Ministry follow-up, to licence revocation that would force the home to close.[92]

118 Inspectors must be members of a specified regulated health profession, with registered nurses and dieticians the most common. Near the end of the first wave in June 2020, the Branch had 152 inspector positions filled, out of a total of 171 available positions. Ministry officials explained to us that maintaining a lower staffing level was a deliberate decision, resulting from internal financial pressure. The Independent Long-term Care COVID-19 Commission also reported that prior to the pandemic and during the first wave, the Inspections Branch had insufficient funding to staff all of the available inspector positions.[93]

119 In addition to inspectors, at the start of the pandemic, the Branch had three long-term care consultant/environmental inspectors to help advise and support inspectors on various matters, including infection prevention and control and emergency plans and incidents. Historically, these specialists were typically brought in at the request of an inspector after receiving approval from a Branch manager. The environmental inspector’s role was mostly to support, advise, and train other inspectors.

On-site inspections

120 Prior to the pandemic, the vast majority of inspections occurred on-site at long-term care homes with inspectors relying on reviewing records, observation, and interviews to make findings. Off-site inspections, which rely solely on document reviews and virtual interviews, were very rare. Typically, inspections would consider a home’s compliance history for the past 36 months. Using relevant “inspection protocols,” inspectors assessed whether the home was complying with specific legislative provisions. Any findings of non-compliance required evidence from at least two of three sources (interviews, observations and reviewing records). If non-compliance regarding a resident issue was found, the inspector had to expand the review to include three more residents.

121 At the end of an inspection, inspectors would debrief with the home and contact complainants within two business days of completion. They then prepared the inspection report and sent it to the home, usually within 20 business days. Within two business days of sharing the inspection report with the home, inspectors were expected to follow up again with any affected complainant.

Identifying “high-risk” homes

122 Prior to March 2020, the Inspections Branch used a number of methods to identify long-term care homes that might be at higher risk of not complying with the law. This helped focus the Branch’s resources and guide its inspection efforts.

123 One of the main tools used was a scorecard called the Long-Term Care Home Performance Report, which helped gauge the performance of long-term care homes over a period of time, using a specific set of resident indicators. This report identified how many times certain events had occurred, such as findings of non-compliance, high-risk compliance orders, and re-issued compliance orders. It did not identify the underlying issue (e.g., infection prevention and control) that led to each event. The Branch typically shared this report with the long-term care sector every three months, but it is not clear what further action, if any, flowed from this communication.

124 The Branch also relied on a document referred to as the “Director’s dashboard” to identify high-risk homes. This was a list of homes and the status of compliance activities where the Inspections Branch Director was directly involved.

125 Inspectors also told us about other ways that the Branch became aware of homes at higher risk of non-compliance, including discussions at team meetings, trends analyses conducted when reviewing new complaints and critical incidents, and general knowledge of how certain homes performed over time.

Stop inspections, effective immediately

126 As Ontario became increasingly concerned about the spread of COVID-19, on March 13, 2020, the practices of the Ministry’s Inspections Branch shifted dramatically. On that Friday, Ontario’s Secretary of Cabinet instructed members of the Ontario Public Service to work from home wherever feasible. The Ministry of Long-Term Care asked the Inspections Branch to adhere to the Secretary’s direction, and service area office managers passed on the news to inspectors. Although the wording differed, the message was clear: All inspections must immediately stop.

127 On Saturday, March 14, the Inspections Branch Director[94] wrote to all inspectors to confirm that employees would be working from home for three weeks. The Director asked for the inspectors’ patience while the Branch figured out a plan.

128 The senior Inspections Branch officials scrambled to come up with a path forward. The plan they ultimately proposed was contained in a slide deck that set out the following information about inspections:

Proactive Inspections – will be suspended during COVID-19

Reactive Inspections:

- Follow-up Inspections – Low-risk [compliance] order follow-up inspections will be postponed. Inspectors will follow up on high-risk orders (e.g., director orders) using off-site inspection processes wherever possible.

- Complaint Inspections – Inspectors will follow up with all complainants and determine level of risk to residents. There has been an increased volume of complaints related to visitor restrictions. Inspectors have been provided with key messages to assist them on these calls. **Highly recommending the importance to maintain contact with the public regarding complaints.

- Critical Incident Inspections – Inspectors will monitor Critical Incident Intakes and triage levels will be assigned. High-risk intakes will be inspected using most appropriate inspection process. Wherever possible off-site inspections will be used.

- High-risk inspections would encompass situations where there is immediate risk to residents.

The slide deck clarified that high-risk cases “may need in-person [inspection]; off-site inspection may be used.”

129 This information was forwarded to the Deputy Minister’s office for approval on March 17, and on March 21, the Deputy Minister learned that Cabinet Office had “no concerns” with the approach and the Inspections Branch had the “green light to move ahead.”

130 Later that same day, the Premier’s Office asked how many inspections the Branch expected to continue doing. The Branch Director replied that they would continue to carry out inspections of high-risk situations, representing approximately 15% of the Branch’s usual inspection volume. The Director’s response did not specify if those inspections would occur on-site or off-site. During his interview with our Office, the Deputy Minister of Long-term Care said that based on the Branch’s plan, he understood that inspectors would be on-site to inspect the high-risk scenarios.

131 However, the Ministry took a different approach. While waiting for Cabinet’s approval of the plan, the Inspections Branch decided inspectors would only conduct off-site inspections, even for high-risk issues, except in the most “extenuating” circumstances. This was reflected in a separate document (the “Ministry of Long-Term Care Inspection Branch Strategy”) drafted by Branch management. The March 16 version of the strategy said:

The inspection process will be conducted off-site and will be risked [sic] focused.

Note: In extenuating circumstances and only with management approval, an inspector may inspect in a home where there is a significant high-risk situation impacting one or more residents in a home. Proper emergency protocols will be applied.

132 On March 18, the Inspections Branch Director told inspectors that low-risk inspection files would be placed “on hold,” and only high-risk inspections (level 3+ and 4 files) would proceed in a “focused” manner.