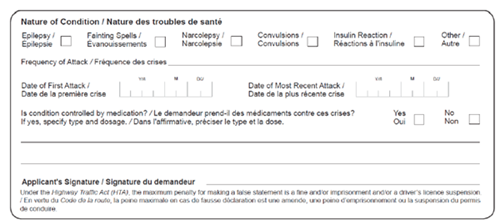

Figure 4: Excerpt from Report on Applicant with a Medical History form. A full copy of this form can be found at Appendix C.

74 If an applicant has not had an insulin reaction in the past year, the Service Ontario office or DriveTest centre can process his or her application. Otherwise, the form is sent to the Ministry’s Medical Review Section and the licence or renewal is delayed pending this review.

75 The Medical Review Section can ask the driver for more information to assess his or her medical condition. Staff in the Medical Review Section may also consult the Ministry’s Driver Improvement Policy Manual 2010, which contains tables showing what steps should be taken if certain medical conditions are identified, depending on the class of licence involved.

76 In the case of an application or renewal of a standard “G-class” driver’s licence, no further action is required. The assumption is that the driver’s condition is under control unless a physician reports otherwise. In the case of a commercial licence, the Ministry requires a specialist report be provided for review. If a commercial licence is granted or renewed, cyclical medical reporting is also instituted.

77 The Ministry recently announced plans to introduce online licence renewal. We were told that under this proposed system, people who indicate they have any of the listed medical conditions will not be able to have their applications processed online, but will be directed to go to a Service Ontario office or DriveTest centre instead.

78 If a driver’s licence is suspended for medical reasons, he or she can request an administrative review through the Medical Review Section or appeal the suspension to the external Licence Appeal Tribunal.

79 It was revealed during Mr. Maki’s trial that his type 1 diabetes was diagnosed in 2000. Ministry records show his first driver’s licence renewal application on which he reported having one of the listed medical conditions was in December 2002.

80 In November 2007, when he renewed his licence again at a Service Ontario office, Mr. Maki noted he had diabetes. However, the form he was given was out of date, and it did not refer specifically to “diabetes requiring insulin to control.” The Ministry took no further action.

81 Mr. Maki should have filled out the proper 2007 form, and should have identified that he had insulin-dependent diabetes. He would then have been asked to fill out a “Report on Applicant with a Medical History” form. If he had then reported having had an insulin reaction within the past year, the form would have been sent to the Ministry’s Medical Review Section for review. However, it is unclear whether Mr. Maki experienced any incidents of insulin reaction around that time, and normal Ministry procedure would not have required follow-up for a general licence.

82 In his decision, Justice Ramsay noted that Mr. Maki had experienced four serious episodes of hypoglycemia in 2002, 2003, 2004 and 2005, and he had apparently experienced hypoglycemia unawareness as well.

83 But the Ministry’s records indicate that none of Mr. Maki’s treating physicians ever reported that his medical condition put his driving ability at risk. The Ministry does not have access to Mr. Maki’s detailed medical history, and was not in a position to give an opinion on whether it should have received medical reporting under s. 203 of the Highway Traffic Act. An expert report prepared in connection with Mr. Maki’s criminal prosecution noted that his home glucose testing log book – dating back about five months prior to the June 2009 accident – showed frequent episodes of both mild and severe hypoglycemia. However, it also said it was unclear whether his physicians were aware of the frequency and severity of his hypoglycemia at that time.

84 The day after the accident, Mr. Maki was released from custody and prohibited from driving as a condition of his bail. Remarkably, the Ministry did not suspend his driver’s licence until January 7, 2011. Our investigation looked at the reasons for this delay.

85 If the reporting system had worked as intended, the emergency room doctor would have alerted the Ministry about Mr. Maki’s uncontrolled hypoglycemia. The police would also have notified the Ministry about the fatal accident and Mr. Maki’s medical condition. These steps would likely have led to immediate licence suspension after review by the Medical Review Section.

86 However, in Mr. Maki’s case, the system clearly broke down.

87 Hamilton police did file a motor vehicle accident report with the Ministry the day after the accident. The section on the report form where police can make note of a driver’s medical or physical condition was marked as “unknown.” The Ministry told us that unless police have specific information about an individual’s medical history, it is common for this section to be marked in this manner. However, if Mr. Maki’s hypoglycemia had been mentioned, the Ministry would likely have required further medical information from Mr. Maki and suspended his licence.

88 Police did not submit a Driver Information/Request for Driver’s Licence review form to the Ministry, which could have alerted the Ministry to Mr. Maki’s medical condition. However, a police officer told us that he wrote to the Ministry on police service letterhead about Mr. Maki on July 1, 2009. He said he indicated in the letter that Mr. Maki had been involved in a fatal accident while experiencing diabetic shock, and asked that Mr. Maki’s licence be suspended. However, the Ministry has no record of ever receiving the letter.

89 The emergency room doctor who treated Mr. Maki on the day of the accident prepared a medical condition report, stating that he had “diabetes or hypoglycemia or other metabolic diseases – uncontrolled.” This report was entered into evidence at Mr. Maki’s trial. It should have been submitted to the Ministry in accordance with s. 203 of the Highway Traffic Act. Normally, once it receives such a report, the Ministry automatically suspends the driver’s licence. The Ministry has no record of ever receiving the report.

90 From April 10 to August 11, 2010, the police were in contact with the Ministry, requesting information about Mr. Maki’s driving record in connection with the criminal charges against him. The Ministry responded to these requests. However, given the nature of the inquiries, they were dealt with by a policy advisor in the Program Management Section who was not connected with the Medical Review Section. These communications did not trigger a licence suspension.

91 The Ministry’s records also show that it received a letter from the police dated October 21, 2010, asking that Mr. Maki’s licence be suspended, given the fatal accident and his medical condition. On November 4, the police followed up with an email, asking how the Ministry would be responding to their request. They also referred to evidence from Mr. Maki’s preliminary hearing, indicating that the emergency room doctor had notified the Ministry about Mr. Maki’s condition.

92 According to emails we reviewed, in November 8, 2010, the Ministry responded that police reports are logged in as “correspondence” and are given lower priority than medical reports. A Ministry official also told the police it might be difficult for the Ministry to suspend Mr. Maki’s licence, given that the incident had occurred more than a year earlier. The Ministry also confirmed it had nothing on file from the emergency room doctor. Later the same day, the Ministry told the police that the most it could do was request an up-to-date assessment from Mr. Maki’s diabetes specialist.

93 On November 8, 2010, the Ministry sent Mr. Maki a letter, asking him to have a Diabetic Assessment form completed and returned within a month and warning that if he failed to do so his licence would be suspended. The Ministry did not receive the requested medical information, and on December 29, 2010, it sent Mr. Maki a notice of suspension effective January 7, 2011.

94 Given that Mr. Maki was already prohibited from driving as a condition of his bail, the impact of the delay in formally suspending his licence is unclear. However, I have concerns about what occurred in his case.

95 The Ministry was unable to explain why Mr. Maki was given an outdated form, which had not been in use for three years, when he renewed his driver’s licence in 2007. The Service Ontario office Mr. Maki visited to renew his licence was privately operated. However, the Ministry should ensure that all offices that issue driver’s licences use up-to-date forms and are familiar with the protocols relating to medical conditions that can affect driving ability.

Recommendation 1

The Ministry of Transportation should ensure that all Service Ontario and DriveTest Centre offices use current versions of forms relating to driver’s licences and are familiar with and follow proper procedures relating to individuals with medical conditions which may render it dangerous for them to drive.

96 Even if Mr. Maki had been provided with the correct licence renewal application and asked to complete a medical history form, there is no guarantee that he would have disclosed sufficient information to enable the Ministry to accurately assess any risk he might have posed. The Ministry relies to a large degree on self-reporting of medical conditions by drivers. The form that the Ministry requires applicants to fill out once they indicate they are insulin-dependent diabetics refers to “insulin reaction.” If they indicate on the form that they have had an insulin reaction within a year of the date of the application, the form is sent to the Medical Review Section.

97 Unfortunately, the term “insulin reaction” is not defined. Unless someone applying for a G-class licence happens to provide expanded information on the form, specifically stating that he or she has uncontrolled diabetes or hypoglycemic unawareness, the form is simply filed once it reaches the Medical Review Section and no further action is taken.

98 The Ministry’s explanation for this practice is that if a driver’s medical condition is serious, his or her treating physician is obligated to give notice under the Highway Traffic Act. At the same time, some Ministry officials acknowledged to us that physicians do not always file reports on their patients as required by the Act. Physicians may also have incomplete or outdated information about the medical status of their patients.

99 Under the circumstances, the Ministry should clarify the instructions on its “Report on Applicant with a Medical History” form with regard to drivers’ insulin reactions. For example, it would be helpful to include descriptions and/or examples of insulin reactions, and such terms as “uncontrolled diabetes/hypoglycemia” and “hypoglycemia unawareness.” The form should also require applicants to provide details about the nature of the “insulin reaction” they have experienced.

Recommendation 2

The Ministry of Transportation should revise its medical history form to provide clearer direction and require greater detail about insulin reactions experienced by drivers.

100 The Medical Review Section should also carefully review the medical history forms forwarded to them. If the nature of the insulin reaction an individual has experienced is not apparent, further information should be obtained and reviewed.

Recommendation 3

The Ministry of Transportation should ensure that its Medical Review Section carefully reviews medical history forms submitted by drivers with diabetes and obtains further information if a driver’s history of insulin reaction is unclear.

101 It is regrettable that the Ministry does not appear to have received the medical and police communications about Mr. Maki, which would have led to more timely suspension of his licence. We were unable to confirm what happened to these reports. However, the Ministry’s new e-filing system for medical reports and e-collision system for police accident reports may help reduce the potential in future for such reports to go astray due to human error.

102 By April 2010, the Ministry was aware that Mr. Maki had been involved in a fatal accident. Despite this, it did nothing to suspend his licence for another seven months. This lapse arose because information did not flow from the Ministry’s Program Management Section to the Medical Review Section. The Program Management Section focused narrowly on issues in its purview and failed to recognize the seriousness of the situation in terms of driver safety. The Ministry assured us that police reports relating to driver safety issues are given equal priority to medical reports. However, it is disturbing, given the facts of the Maki case, that a Ministry official would suggest that the Ministry assigned lower priority to police reports.

103 The Ministry should ensure that in future its staff members do not function in silos. There should be greater co-ordination and communication between the Medical Review Section and other operational areas. The Ministry should also educate staff on the importance of acting swiftly when information about driver safety is raised, regardless of whether it comes from police or a medical practitioner.

Recommendation 4

The Ministry of Transportation should educate its staff on the importance of communicating immediately with the Medical Review Section whenever issues of driver safety based on medical conditions are raised.

104 Our review of the Ministry’s processes for obtaining and assessing information about medical conditions that might affect a driver’s capacity also identified several additional areas of concern.

105 Despite the fact that the Canadian Council of Motor Transport Administrators standards were updated in August 2011, the Ministry initially sent us the old 2009 standards in response to our request for documentation relevant to this investigation. In addition, during our interviews, Ministry staff in the Medical Review Section provided conflicting answers about the standards that were currently in use. It is important for the Ministry to apply the latest standards consistently when assessing the safety of drivers in Ontario.

Recommendation 5

The Ministry of Transportation should ensure that all staff in the Medical Review Section are provided with ongoing training to ensure they are familiar with and apply current Canadian Council of Motor Transport Administrators standards for driving.

106 One Ministry official also told us the Ministry was considering linking to the Council’s standards from its website. The driving public as well as medical practitioners should have easy access to the standards. This would assist the public and physicians in understanding the reasoning behind licence suspension and reinstatement on medical grounds. As well, given that the standards are relatively complex, it would be useful for the Ministry to provide an explanation of the standards and their relevance to evaluation of driver safety, in addition to a link.

Recommendation 6

The Ministry of Transportation should ensure that a link to the standards used to assess the medical fitness of drivers and a summary of their relevance are available on its website.

107 There are multiple resource documents that physicians and Ministry staff can consult when assessing how diabetes affects a person’s ability to drive safely. There are the standards developed by the Canadian Council of Motor Transport Administrators and the guide produced by the Canadian Medical Association. The Canadian Diabetic Association has also issued guidelines for drivers with diabetes.

108 The available reference materials differ in their level of detail as well as in their treatment of the subject. An endocrinologist on the Ministry’s Medical Advisory Committee told us there is considerable confusion in the medical community over what standards should be applied. It seems clear that physicians and Ministry staff would benefit from a single consolidated resource for assessing the safety risk of drivers with diabetes, based on recent medical studies. The Ministry should conduct research and consult the medical community and stakeholders, including the Canadian Diabetic Association, with a view to developing a current, clear, and consistent guideline for use in assessing driving risks associated with diabetes and hypoglycemia. This guide should be available to physicians and the public through the Ministry’s website and other means of distribution.

Recommendation 7

The Ministry of Transportation should engage in research and consultation with a view to developing a clear, comprehensive, and publicly available guide for evaluating the driving risks posed by people living with have diabetes who experience hypoglycemia.

109 Under the Highway Traffic Act medical practitioners are responsible for notifying the Ministry about patients whose medical conditions might adversely affect their ability to drive. Physicians who fail to comply with this obligation are not penalized under the Act, but could be subject to civil liability. In 1985, a cyclist was struck and killed in Etobicoke by a driver who had epilepsy. In ruling on the subsequent lawsuit, Justice Janet Lang Boland of the Ontario Court of Justice concluded that two of the driver’s physicians had been negligent in failing to notify the Ministry about the risk posed by his condition.[22]

110 Similarly, the Ontario Court of Appeal ruled in 1994 that two Hamilton-Niagara-area physicians were negligent for failing to report that a driver had cervical spondylosis, before he was involved in a 1983 motor vehicle accident that seriously injured others. The doctors led evidence at trial that it was not the prevailing practice for physicians to report every incident where a medical condition might impact driving. In dealing with this argument, the Ontario Court of Appeal observed:

The appellants argue that s. 177 (now 203) does not give rise to a cause of action and evidence was tendered by medical experts that it was not the practice to report all incidents. That is, that somehow the medical practice overcame the statutory requirement. … we cannot accept that argument. If the burden is too onerous, it should be amended by the Legislature. We also think it is clear that the duty of doctors to report is a duty owed to members of the public and not just to the patient. It is clearly designed to protect not only the patient but people he might harm if permitted to drive.[23]

The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario told us that physicians are educated about their reporting obligations in medical school and information about reporting requirements is available on the College’s website. The Canadian Medical Association has also produced a guide for physicians entitled Determining Medical Fitness to Operate Motor Vehicles: CMA Driver’s Guide.

111 We interviewed Dr. Donald Redelmeier, a professor from the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Toronto, who has co-authored articles relating to fitness to drive, motor vehicle crashes involving people living with diabetes, and physician reporting.[24] He notes that a variety of factors contribute to physicians’ uncertainty about reporting patients, including concern about patient dissatisfaction, limited time and training, and lack of knowledge about patients’ driving habits. Dr. Redelmeier told us that underreporting of patients is not as prevalent today as it was years ago, given the change to the OHIP schedule allowing physicians to bill for reports. However, he said despite the Highway Traffic Act’s expansive language, only a tiny fraction of drivers – fewer than .5% – are reported to the Ministry, far below the prevalence rates of many diseases that can affect driving. He observed that intermittent disabilities present challenges for reporting, and that the sheer breadth of the reporting requirement makes it difficult for doctors to comply strictly with the law.

112 Representatives of the Ontario Medical Association also told us one of the biggest impediments to physician reporting under the Highway Traffic Act is the broad nature of the obligation and the lack of clear guidelines.

113 The government attempted to improve this in 2002 and 2003, through proposed amendments to the Act that would have provided for regulations to specify the conditions that must be reported by medical practitioners, including functional or visual impairments that might make it dangerous to drive. However, the bills promoting these changes never proceeded past first reading.[25] In 2009, the Ministry consulted with the Ontario Medical Association about once again amending the reporting requirements, but this initiative did not move forward.

114 The Ministry’s present view is that the reporting obligation should lie with physicians, who are best placed to assess the individual circumstances affecting their patients’ ability to drive. The physician’s obligation is to report the patient and the Ministry’s is to make the call on whether the licence should be suspended.

115 The Ministry has engaged in some outreach efforts in the medical community, primarily through submitting articles to the Ontario Medical Association’s Ontario Medical Journal and by providing information, upon request, to provincial medical schools about the duty to report under the Highway Traffic Act. However, senior officials at the Ministry acknowledged to us that physician underreporting of unsafe drivers is still an issue and that additional outreach would be useful. An endocrinologist on the Medical Advisory Committee echoed this sentiment. Given the Ministry’s significant reliance upon medical practitioners to bring concerns about drivers to its attention, it should take more proactive steps to ensure they know their obligations.

Recommendation 8

The Ministry of Transportation should engage in regular outreach to the medical community to enhance its understanding of the responsibility to notify the Ministry about drivers whose medical conditions pose safety risks.

116 As several members of the medical community told us in interviews, the scope of the duty to report conditions that “may make it dangerous” to drive is far-reaching, open to considerable interpretation, and may be out of step with the realities of medical practice. It would be beneficial if additional and clearer guidance could be provided to medical practitioners about what their duty means in practical terms when they see patients with medical conditions such as uncontrolled diabetes and hypoglycemia. The Ministry should engage medical professionals in a dialogue about what measures might better assist them in meeting their reporting obligations, and consider amending the law to reflect these measures.

Recommendation 9

The Ministry of Transportation should, in consultation with the medical community, provide additional guidance to medical practitioners relating to the duty to report their patients under the Highway Traffic Act, and consider whether legislative amendment is required to clarify the reporting obligation.

117 Along with requiring “legally qualified medical practitioners” to report patients, the Highway Traffic Act also protects them from being sued for doing so (s.203(2)). The phrase “legally qualified medical practitioner” is defined in the Legislation Act, 2006, as meaning a member of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (s. 87).

118 Mr. Maki, like many patients these days, received some of his medical care from a nurse practitioner. According to the Nurse Practitioner Association of Ontario, nurse practitioners are primary care providers who see patients with diabetes and provide information relating to their condition. They diagnose, manage medication and monitor patients and can provide comprehensive care, promote patient self-management and educate patients about their obligations when driving.

119 Nurse practitioners are authorized to complete two Ministry forms on behalf of their patients: The standard medical form for commercial drivers or drivers wishing to upgrade their licence, and the substance abuse assessment form, which must be completed when physicians report substance abuse and/or dependence in connection with certain impaired driving offences. However, nurse practitioners are not required to report patients to the Ministry whose medical conditions may make it unsafe for them to drive.

120 In British Columbia, nurse practitioners as well as psychologists are required to report such drivers.

121 The Nurse Practitioners’ Association of Ontario told us that nurse practitioners occasionally report patients, with their knowledge, to the Ministry. However, this is done on an individual and ad hoc basis. An Association representative told us that they have been told by Ministry officials that nurse practitioners might incur liability for reporting patients unless they are expressly covered by the legislation.

122 As the involvement of nurse practitioners in patient care continues to increase in Ontario, their exclusion from the mandatory reporting requirement appears anachronistic. It is in the public interest to ensure that all qualified nurse practitioners have the same obligations and protection from liability as physicians when it comes to reporting patients who present a driving risk. The Ministry should also review the experience of other jurisdictions and expand the reporting requirement to other professionals who may have legitimate concerns about how patients’ conditions affect their capacity to drive.

Recommendation 10

The Ministry of Transportation should take all necessary steps to extend the mandatory medical reporting requirements under the Highway Traffic Act to qualified nurse practitioners and other health care professionals.

123 In addition to acting on medical professionals’ reports about patients, three provinces – Alberta, British Columbia and Saskatchewan – also consider information from concerned members of the public about potentially unsafe drivers. In these jurisdictions, information communicated by citizen whistleblowers can result in additional inquiries to confirm someone is fit to drive. In British Columbia, the Office of the Superintendent of Motor Vehicles receives and assesses unsolicited reports about drivers from paramedics, chiropractors, family members and private citizens. If deemed appropriate, the Office will contact the driver for more medical information.

124 Ministry officials in Ontario told us they do not act on citizen concerns about drivers, but refer them to local police services. The Ministry expressed reluctance to encourage citizens to come forward because such an approach would likely trigger frivolous and vexatious reports.

125 Family members, neighbours, colleagues, and health care providers other than physicians could have relevant information about the demonstrable impact of a medical condition on someone’s driving. Physicians might not have access to this information or might overlook their reporting obligation for various reasons. While it is conceivable that some people might misuse a citizen reporting system, this does not necessarily justify ignoring the concept altogether. Our Office has received complaints from people whose concerns about drivers have been disregarded by the Ministry. With proper planning, the Ministry should be able to implement a process for acting on citizen reports of at-risk drivers that balances the need to protect people from meritless inquiries with the broader interests of public safety. Accordingly, the Ministry should consult with other jurisdictions and review best practices with a view to developing procedures for receiving and acting on information about potentially unsafe drivers from members of the public.

Recommendation 11

The Ministry of Transportation should develop a procedure for receiving and acting on citizen reports of unsafe driving.

126 When a physician reports to the Ministry that a patient has uncontrolled diabetes or hypoglycemia, the Ministry requires the physician to complete its Diabetic Assessment form. Usually, the driver’s licence is immediately suspended and the Medical Review Section reviews the completed form to assess whether it should be reinstated.

127 The Diabetic Assessment Form includes a section on “diabetic education,” where the physician must note when the patient completed this education and whether any further education is recommended. It also allows for a “certificate of completion of diabetic education” to be submitted with the form (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Excerpt from the Diabetic Assessment form. A full copy of this form can be found at Appendix F.

128 We reviewed 126 cases involving drivers who experience complications of diabetes. In 15 of them, treating physicians did not fill out this section of the form, left it incomplete or merely stated that the education was ongoing. In others, no certificate of diabetic education completion was provided to the Ministry. The Ministry’s records reveal there was no follow-up in these cases. Based on our interviews with medical analysts in the Medical Review Section, it appears they do not normally attempt to verify whether drivers have completed diabetes education in these circumstances.

129 We were told that Ministry staff generally would only ask for more information if the physician states on the Diabetic Assessment form that the driver requires re-education or if the file is referred to the Medical Advisory Committee and the Committee recommends it. Out of the 126 Medical Advisory Committee files we reviewed, there were 25 where the driver’s treating physician recommended re-education – but the Ministry followed up in only four. In 13 of the cases we reviewed, the Medical Advisory Committee recommended that the Ministry obtain proof that the drivers had undergone diabetes education or re-education before their licences were reinstated. The Ministry followed up in 10 of these cases.

130 A member of the Medical Advisory Committee told us that if a physician states on the form that a driver requires re-education, then it is the physician’s obligation to send the patient for further education.

131 Diabetes education is key in helping people control their diabetes and in promoting safe driving practices. The questions on the Ministry’s Diabetic Assessment form reflect this. However, the form is of limited value if the Ministry does not ensure that the information it receives is complete and that education takes place as recommended.

132 The Ministry should direct staff in the Medical Review Section to confirm that drivers have received diabetes education, if it is not apparent from the Diabetic Assessment forms. They should also ensure that re-education of drivers has taken place when recommended by the driver’s physician or the Medical Advisory Committee.

Recommendation 12

The Ministry of Transportation should direct staff in the Medical Review Section to confirm that drivers have received diabetic education in cases where this is unclear from the Diabetic Assessment form, and where re-education is recommended by a treating physician or the Medical Advisory Committee.

133 Although information on driving safety is included in diabetes education, the Ministry has not consulted with education providers about the standards the Ministry applies when assessing risks posed by drivers with diabetes. Ministry staff, including medical analysts and senior officials, also told us they were unfamiliar with the actual content of the curriculum delivered by diabetes educators relating to driving risks and safety precautions. An endocrinologist on the Medical Advisory Committee with experience in diabetes education expressed the view that the quality of education provided in different diabetes education centres was “extremely variable.”

134 We reviewed some of the pamphlets that Diabetes Education Centres and hospitals in the province distribute to patients about diabetes and driving. The level of information ranged from a one-page tip sheet to a detailed explanation of driver obligations and the impact of hypoglycemia.

135 Given the importance of diabetic education in mitigating driving risks, it is in the public interest for the Ministry of Transportation to be proactive in this area. It should establish a partnership with the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care and consult with that Ministry as well as diabetes education providers. In addition to sharing information about the standards it uses in evaluating driver safety, the Ministry should take steps to ensure that educators across the province provide consistent and accurate information about promoting safe driving for individuals with diabetes.

Recommendation 13

The Ministry of Transportation should establish a partnership with the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care and consult with diabetes education providers, the Canadian Diabetes Association and other stakeholders with a view to sharing information about the standards it uses to evaluate driver safety.

Recommendation 14

The Ministry of Transportation should take proactive steps to ensure diabetes education is consistent and accurate across the province in promoting safe driving for individuals with diabetes.

136 The Ministry’s website does not contain specific materials relating to diabetes and driving. At a minimum, it should provide links on its website to useful resources such as the online information about diabetes available through the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

Recommendation 15

The Ministry of Transportation should include information on its website about diabetes and driving, as well as the risks associated with hypoglycemia, including links to useful resources such as the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care’s online information on diabetes.

137 In Mr. Maki’s case, he had received diabetic education and was familiar with the risks associated with driving. While his own home testing records indicated that he was experiencing frequent hypoglycemic incidents, his medical practitioners were not necessarily aware of this, and it is unclear whether their reporting obligation would have been triggered under the circumstances. Like a driver who chances having one more drink before getting behind the wheel, Mr. Maki made a fatal choice to drive without confirming that his blood sugar levels were stable. Medical practitioners are limited in their contact with their patients, and often rely on the information that is conveyed to them. Individual drivers bear significant responsibility to ensure they drive safely. As one of the endocrinologists on the Ministry’s Medical Advisory Committee remarked to us, the Ministry has waged an aggressive and high-profile campaign to alert drivers to the risks of drinking and driving. Yet it has not taken a similar approach to raise awareness of the often comparable risks that can be presented by some medical conditions.

138 The Ministry should make additional public outreach and education efforts to underscore drivers’ responsibility to take all reasonable precautions when they have medical conditions that might affect them behind the wheel. Mr. Maki’s case should be used as a cautionary tale to illustrate the risks associated with hypoglycemia and driving.

Recommendation 16

The Ministry of Transportation should launch an education campaign to alert individuals with medical conditions that may pose safety risks for driving, such as uncontrolled diabetes/hypoglycemia, and use Mr. Maki’s case as an example.

139 Both endocrinologists on the Ministry’s Medical Advisory Committee told us that in their experience, treating physicians rarely fully complete their patients’ Diabetic Assessment forms.

140 They said they are often unable to tell from the form why a patient developed hypoglycemia, which is key to evaluating safety risks. They expressed the view that the two lines on the form where physicians are asked to describe the circumstances surrounding a hypoglycemic reaction are insufficient to capture the necessary information. This brevity may lead to important information being omitted.

141 They also emphasized the importance of reviewing a driver’s blood glucose logs in assessing fitness to drive – and noted that in some cases it is clear the treating physicians have not done so as required. Of the 126 files we received, the committee asked for copies of the driver’s blood glucose logs in 31. The committee required these to be presented in digital form from an electronic meter, (digital records are viewed as more reliable because they are less susceptible to manipulation than manual records). In the past, the Ministry required drivers to submit blood glucose logs to have their licences reinstated – but this practice was abandoned because of health and safety concerns relating to blood residue on handwritten logs. Today, when completing the Ministry’s Diabetic Assessment form, physicians are required to review a patient’s blood glucose reading for the preceding 30 days and answer questions relating to the results.

142 In its latest review of the Diabetic Assessment form, the Ministry should carefully consider the advice of experts in endocrinology, and ensure that the form encourages physicians to provide the best and most accurate information available, in order to enable objective and complete evaluation of their patients’ fitness to drive.

Recommendation 17

The Ministry of Transportation should consider the advice of experts in the field of endocrinology in revising its Diabetic Assessment form, and ensure that the form contains sufficient space to allow for complete details to be provided and encourages review of blood glucose logs.

143 In any case, where the information on a completed Diabetic Assessment form suggests that a physician has not adequately reviewed a patient’s blood glucose logs, the Ministry should require them to be submitted for review by the Medical Advisory Committee.

Recommendation 18

The Ministry of Transportation should require submission of blood glucose logs in all cases where it is unclear from the Diabetic Assessment form that a physician has adequately reviewed them.

144 Three lives were lost on June 26, 2009, when Allan Maki made the fatal choice of driving before ensuring that his blood glucose levels were stable. While Mr. Maki was clearly the author of this misfortune, my investigation revealed that the Ministry of Transportation’s system for obtaining and assessing information relating to drivers experiencing uncontrolled hypoglycemia is deficient. While the Ministry has taken some positive steps, including introducing electronic reporting to simplify and to reduce the likelihood of error in reporting at-risk drivers, additional improvements are necessary.

145 My investigation revealed that lack of co-ordination within the Ministry contributed to inordinate delay in suspending Mr. Maki’s licence. It also highlighted uncertainty about the standards the Ministry applies to assess driver safety, that the system for reporting at-risk drivers and for obtaining details of medical conditions fails to capture relevant information and is unclear, and that enhanced outreach efforts are necessary to ensure consistent and accurate education of at-risk drivers, the public and the medical community. The potential for catastrophic accidents involving drivers with conditions such as uncontrolled hypoglycemia might have been diminished had the Ministry been more proactive in promoting and monitoring driver safety.

146 It is my opinion that the Ministry’s failure to ensure timely suspension of Mr. Maki’s licence was unreasonable and wrong, under the Ombudsman Act. Its failure to take additional proactive measures to ensure the effectiveness of its system for reporting of medical conditions and encouraging driver safety is also unreasonable and wrong under the Act.

147 Accordingly, I am making the following recommendations, which I am hopeful will improve safety on Ontario’s roads:

Recommendation 1

The Ministry of Transportation should ensure that all Service Ontario and DriveTest Centre offices use current versions of forms relating to driver’s licences and are familiar with and follow proper procedures relating to individuals with medical conditions which may render it dangerous for them to drive.

Recommendation 2

The Ministry of Transportation should revise its medical history form to provide clearer direction and require greater detail about insulin reactions experienced by drivers.

Recommendation 3

The Ministry of Transportation should ensure that its Medical Review Section carefully reviews medical history forms submitted by drivers with diabetes and obtains further information if a driver’s history of insulin reaction is unclear.

Recommendation 4

The Ministry of Transportation should educate its staff on the importance of communicating immediately with the Medical Review Section whenever issues of driver safety based on medical conditions are raised.

Recommendation 5

The Ministry of Transportation should ensure that all staff in the Medical Review Section are provided with ongoing training to ensure they are familiar with and apply current Canadian Council of Motor Transport Administrators standards for driving.

Recommendation 6

The Ministry of Transportation should ensure that a link to the standards used to assess the medical fitness of drivers and a summary of their relevance are available on its website.

Recommendation 7

The Ministry of Transportation should engage in research and consultation with a view to developing a clear, comprehensive, and publicly available guide for evaluating the driving risks posed by people living with have diabetes who experience hypoglycemia.

Recommendation 8

The Ministry of Transportation should engage in regular outreach to the medical community to enhance its understanding of the responsibility to notify the Ministry about drivers whose medical conditions pose safety risks.

Recommendation 9

The Ministry of Transportation should, in consultation with the medical community, provide additional guidance to medical practitioners relating to the duty to report their patients under the Highway Traffic Act, and consider whether legislative amendment is required to clarify the reporting obligation.

Recommendation 10

The Ministry of Transportation should take all necessary steps to extend the mandatory medical reporting requirements under the Highway Traffic Act to qualified nurse practitioners and other health care professionals.

Recommendation 11

The Ministry of Transportation should develop a procedure for receiving and acting on citizen reports of unsafe driving.

Recommendation 12

The Ministry of Transportation should direct staff in the Medical Review Section to confirm that drivers have received diabetic education in cases where this is unclear from the Diabetic Assessment form, and where re-education is recommended by a treating physician or the Medical Advisory Committee.

Recommendation 13

The Ministry of Transportation should establish a partnership with the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care and consult with diabetes education providers, the Canadian Diabetes Association and other stakeholders with a view to sharing information about the standards it uses to evaluate driver safety.

Recommendation 14

The Ministry of Transportation should take proactive steps to ensure diabetes education is consistent and accurate across the province in promoting safe driving for individuals with diabetes.

Recommendation 15

The Ministry of Transportation should include information on its website about diabetes and driving, as well as the risks associated with hypoglycemia, including links to useful resources such as the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care’s online information on diabetes.

Recommendation 16

The Ministry of Transportation should launch an education campaign to alert individuals with medical conditions that may pose safety risks for driving, such as uncontrolled diabetes/hypoglycemia, and use Mr. Maki’s case as an example.

Recommendation 17

The Ministry of Transportation should consider the advice of experts in the field of endocrinology in revising its Diabetic Assessment form, and ensure that the form contains sufficient space to allow for complete details to be provided and encourages review of blood glucose logs.

Recommendation 18

The Ministry of Transportation should require submission of blood glucose logs in all cases where it is unclear from the Diabetic Assessment form that a physician has adequately reviewed them.

Recommendation 19

The Ministry of Transportation should report back to my Office in six months’ time on the progress of implementing my recommendations and at six-month intervals thereafter until such time as I am satisfied that adequate steps have been taken to address them.

148 The Ministry of Transportation was provided with an opportunity to make representations concerning my preliminary findings, opinion and recommendations. On March 28, 2014, the Ministry responded, accepting all of my recommendations and providing a chart detailing the steps it intends to take to address them. A copy of the Ministry’s response is attached at Appendix G.

149 The Ministry expects to implement most of my recommendations in September 2014. However, physician and public education about drivers living with diabetes (Recommendations 8 and 16) and legislative changes to expand medical reporting requirements (Recommendations 9 and 10) are ongoing initiatives. The Ministry explained that expanding the range of medical practitioners who must report drivers requires enabling legislation to be passed and further consultation with the medical community.

150 On March 17, 2014, the Minister of Transportation introduced Bill 173, Highway Traffic Amendment Act (Keeping Ontario’s Roads Safe), 2014. The bill proposes amendments to the Highway Traffic Act that would enable future regulations to clarify medical conditions that must be reported and allow additional medical professionals to report drivers who have medical conditions that may make them unsafe drivers.

151 I am pleased with the Ministry’s positive response to my report, and the efforts it has already made towards implementation of my recommendations. The Ministry has committed to providing semi-annual updates on its progress, and I will monitor them closely.

_____________________

André Marin

Ombudsman of Ontario

This link opens in a new tabA- Medical Condition Report (PDF)

This link opens in a new tabB - Application for Driver’s Licence / Licence Renewal (PDF)

This link opens in a new tabC - Report on Applicant with a Medical History (PDF)

This link opens in a new tabD - Driver Information / Request for Driver’s Licence Review (PDF)

This link opens in a new tabE - Medical Report (PDF)

F - Diabetic Assessment (PDF)

This link opens in a new tabG - Response to Ombudsman findings, March 28, 2014 (PDF) | This link opens in a new tabchart (accessible PDF)

[1] British Columbia (Superintendent of Motor Vehicles) v. British Columbia (Council of Human Rights), [1999] 3 S.C.R. 868 at page 6.

[2] R v. Allan Maki, Superior Court of Justice, unreported reasons of judgment, December 8, 2011.

[3] This link opens in a new tabhttp://www.ices.on.ca/webpage.cfm?site_id=1&org_id=31&morg_id=0&gsec_id=0&item_id=7448; see also This link opens in a new tabhttp://www.ices.on.ca/webpage.cfm?site_id=1&org_id=31&morg_id=0&gsec_id=0&item_id=1312

[4] Canadian Council of Motor Transport Administrators, This link opens in a new tabDetermining Driver Fitness in Canada, Edition 13 August 2013 Chapter 7: Diabetes - Hypoglycemia at page 159.

[5] Ibid, at page 158

[6] This link opens in a new tabhttp://www.diabetes.ca/documents/about-diabetes/112022_managing-your-blood-glucose_0413_lc_final.pdf

[7] This link opens in a new tabhttp://www.diabetes.ca/files/StayHealthy.pdf

[8] Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee, This link opens in a new tabHypoglycemia: Chapter 14, Dale Clayton MHSc, MD, FRCPC Vincent Woo MD, FRCPC Jean-François Yale MD, CSPQ, FRCPC.

[9] This link opens in a new tabhttp://www.mayoclinic.com/health/diabetic-hypoglycemia/DS01166/DSECTION=symptoms

[10] This link opens in a new tabhttp://www.diabetes.ca/diabetes-and-you/living/guidelines/commercial-driving/

[11] Ibid.

[12] CCMTA Standards, supra note 4 at page 161.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid, at page 162.

[16] Ibid, at page 161.

[17] This link opens in a new tabhttp://www.diabetes.ca/diabetes-and-you/living/guidelines/commercial-driving/

[18] Figures are not yet available for the 2012.

[19] A copy of the Diabetic Assessment Form is attached in Appendix F.

[20] This link opens in a new tabhttp://www.ccmta.ca/english/producstandservices/publications/publications.cfm

[21] A complete copy of the Application for Ontario Driver’s Licence and Driver’s Licence Renewal Application are attached in Appendix B.

[22] Spillane v. Wasserman, [1992] O.J. No. 2607.

[23] Toms v. Foster [1994] O.J. No. 1413.

[24] Mandatory Reporting by Physicians of Patients Potentially Unfit to Drive (2008) Open Medicine 2008;2(1) : E8-17 Donald A. Redelmeier, Vikram Vinkatesh, Matthew B. Stanbrook. Motor Vehicle Crashes in Diabetic Patients with Tight Glycemic Control: A Population-based Case Control Analysis (2009) PLoS Medicine December 2009 / Volume 6 / Issue 12 / e1000192 Donald A. Redelmeier, Anne B. Kenshole , Joel G. Ray; Physicians’ Warnings for Unfit Drivers and the Risk of Trauma from Road Crashes (2012) N ENGL J MED 367;13 September 27, 2012, Donald A. Redelmeier, M.D., M.S.H.S.R., Christopher J. Yarnell, A.B., Deva Thiruchelvam, M.Sc., and Robert J. Tibshirani, Ph.D.

[25] Bill 241, Road Safety Act, 2002, Bill 20, Road Safety Act, 2003.